This paper introduced herein reveals the essential difference in generalization ability—i.e., cross-scenario application and learning capability—between humans and artificial intelligence (AI). This achievement holds critical guiding significance for the clinical application of embryo image algorithms, helping embryologists clearly understand the advantages and limitations of AI, optimize human-AI collaboration models, and improve the accuracy of embryo selection.

Ilievski, F., Hammer, B., van Harmelen, F. et al. Aligning generalization between humans and machines. Nat Mach Intell 7, 1378–1389 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01109-4

1. Core Difference in Human-AI Learning Ability: A Concrete Reflection in Embryo Assessment Scenarios

The paper explicitly states that the connotation of “generalization” differs fundamentally between humans and AI, and this difference is particularly prominent in embryo assessment.

Embryologists’ generalization relies on “causal common sense and conceptual abstraction.” Through a small number of typical samples (e.g., day-3 embryos with 8 cells and <5% fragmentation rate), they can extract the core characteristics of “high-quality embryos” and form a flexible judgment framework. When facing atypical embryos (e.g., day-3 embryos with 7 cells but uniform size), they can make reasonable assessments based on the causal logic that “cleavage rate reflects developmental activity.” Meanwhile, they inherently exhibit robustness to imaging noise (e.g., microscope halos) and image deviations caused by equipment differences, and can automatically focus on core indicators such as cell activity and cleavage synchrony.

AI’s generalization, by contrast, is based on “statistical pattern induction.” Current AI systems for embryo imaging (e.g., models based on convolutional neural networks) build models by learning the correlation between “pixel distribution and high-quality labels.” For example, they may memorize the statistical rule that “round contour + uniform cell size → high quality,” but fail to understand the essential logic of embryonic development. Additionally, AI has the limitation of “relying on the distribution of training data”—when the training set lacks samples such as “high-quality 7-cell embryos” or “slightly irregular embryos,” AI is prone to misjudgment; changes in data distribution caused by switching imaging equipment can also significantly reduce the accuracy of assessment.

2. Three-Dimensional Framework of Human-AI Learning Differences

2.1 Learning Process: Human Rule Extraction vs. AI Data Accumulation

Embryologists’ generalization process follows a conceptual leap of “abstraction – expansion – analogy”: first, they abstract the core rules of “high-quality embryos” from specific samples, then extend these rules to atypical cases, and finally adjust judgments by analogy with past clinical experience.

AI’s generalization process, however, is “data-driven pattern fitting.” It can only induce pixel correlations within training data and cannot achieve conceptual migration, resulting in poor adaptability to unseen embryo morphologies or imaging scenarios.

2.2 Learning Outcomes: Human Interpretable Rules vs. AI Implicit Parameter Matrices

The product of embryologists’ generalization is “interpretable clinical rules,” such as “multinucleated cells indicate the risk of chromosomal abnormalities” or “fragmentation rate >10% requires cautious assessment.” These rules can be clearly articulated, revised, and transmitted.

The product of AI’s generalization is “implicit probability distributions and model parameters.” Its assessment logic cannot be converted into clinically understandable rules—when AI classifies an embryo as “high-quality,” it usually cannot clearly explain the core basis for this judgment, which limits clinical trust in AI results.

2.3 Cross-Scenario Application: Human Anti-Interference Stability vs. AI Distribution Sensitivity

Generalization operators refer to the ability to apply generalized products to process new data. Embryologists can ignore interferences such as differences in imaging quality or embryo position shifts, and make stable judgments based on core developmental characteristics.

AI, by contrast, is extremely sensitive to “out-of-distribution (OOD) data.” Once the distribution of new data differs from that of the training data (e.g., switching microscopes or encountering rare embryo morphologies), its performance will decline significantly.

3. Clinical Optimization Pathways for Embryo Image AI

Based on the “human-AI generalization alignment” concept proposed in the paper and combined with clinical needs for embryo assessment, AI application can be optimized from three aspects:

3.1 Building a “Clinical Rule Module” for AI

Integrate embryologists’ clinical rules with AI’s feature extraction capabilities. Encode rules such as “cleavage synchrony = high quality” or “multinucleation = risk” into symbolic modules, while using AI to extract fine-grained features of embryo images (e.g., fragmentation distribution, cell edge clarity). Through cross-module fusion, realize collaborative assessment of “rule filtering – feature fine evaluation” to achieve abstraction ability closer to that of humans.

This approach can reduce AI’s reliance on massive labeled data, improve the accuracy of judgments on atypical embryos, and align the assessment logic more closely with clinical cognition.

3.2 Enabling AI to Learn “Typical Embryo Prototypes”

Have senior embryologists label a “prototype library of embryos” (e.g., “high-quality 8-cell type,” “potential 7-cell type,” “multinucleated risk type”). Enable AI to assess new embryos by comparing their structural similarity with prototypes in the library, and revise results by combining clinical rules.

This method simulates humans’ ability to learn from typical cases, addresses the clinical challenges of scarce high-quality embryo samples and difficulty in obtaining rare morphology samples, and reduces AI’s reliance on data volume.

3.3 Establishing a “Human-AI Collaboration Feedback Loop”

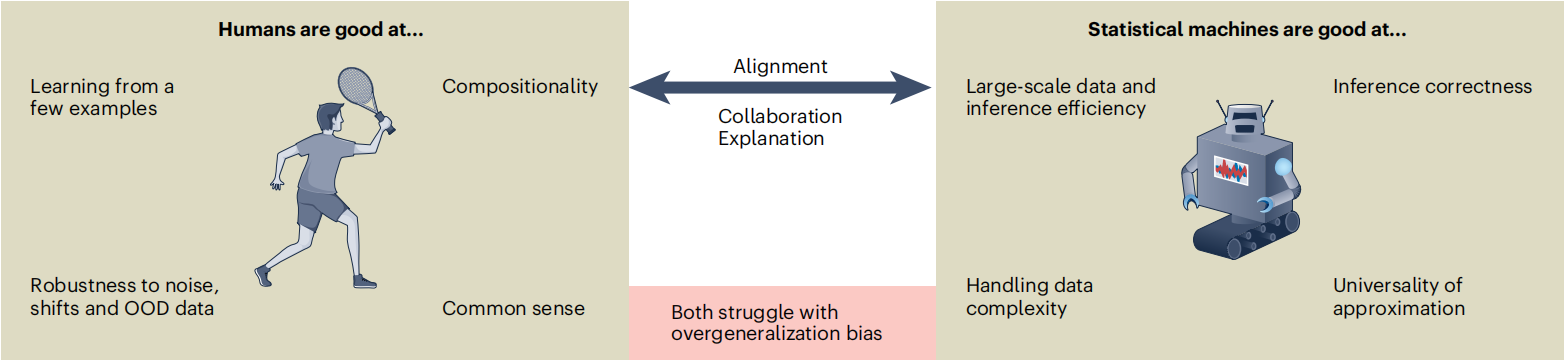

The essential difference between human and AI generalization means that alignment must rely on collaboration: humans excel at conceptual abstraction and common sense judgment, while machines excel at large-scale processing and pattern recognition. The two need to complement each other through feedback mechanisms.

For example:

- AI first conducts preliminary screening of massive embryo images and flags cases with low prediction confidence (e.g., embryos with special morphologies or blurry imaging).

- Embryologists perform professional labeling on these cases and supplement judgment bases (e.g., “Although this oval embryo has an atypical morphology, its cleavage is synchronous and it has developmental potential”).

- AI updates its generalization rules based on this feedback, gradually narrowing the gap with human judgment logic, and forming a collaborative model of “AI efficient preprocessing – human accurate decision-making.”

4. Conclusion: Human-AI Collaboration Is the Core Clinical Positioning of Embryo Image AI

The value of embryo image AI lies in efficiently processing massive images and mining potential features, but its generalization ability cannot fully match the flexible judgment of embryologists, which is based on causal common sense and clinical experience.

In future clinical applications, the goal of “human-AI generalization alignment” must be pursued: while retaining the technical advantages of AI, integrate professional embryology knowledge. Embryologists, based on their understanding of human-AI differences, can reasonably position AI’s role and enhance the efficiency and accuracy of embryo selection through complementary advantages, providing technical support for clinical practice in assisted reproduction.