This paper introduces an innovative foundational model for in vitro fertilization (IVF) embryo assessment—FEMI. By leveraging self-supervised learning to extract universal features from a vast collection of unannotated time-lapse embryo images, the study provides a robust pre-trained foundation for multiple clinical tasks. FEMI demonstrates exceptional performance in critical applications such as ploidy prediction and blastocyst quality scoring, significantly reducing reliance on manually labeled data. However, its data sources are primarily concentrated in high-resource centers, lacking representation from low- and middle-income regions and older patients, which limits the model’s applicability in broader clinical scenarios.

Reference

Rajendran, S., Rehani, E., Phu, W. et al. A foundational model for in vitro fertilization trained on 18 million time-lapse images. Nat Commun 16, 6235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61116-2

Research Background: Practical Dilemmas of Traditional Embryo Assessment

The success rate of IVF is highly dependent on the accuracy of embryo selection, but existing methods face three major challenges: Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy (PGT-A) is costly and invasive; global embryo scoring standards are inconsistent, leading to significant variability in subjective judgments among embryologists; and current AI tools can only address single tasks while requiring large volumes of manually labeled data. These issues ultimately result in potential misjudgment of high-quality embryos, imposing unnecessary economic and emotional burdens on patients. This study introduces the concept of “foundational models” into reproductive medicine, enabling AI to independently learn the laws of embryonic development from 18 million unannotated time-lapse images through self-supervised learning, which is then transferred to multiple clinical tasks. The goal is to establish a non-invasive, standardized, and reusable embryo assessment system.

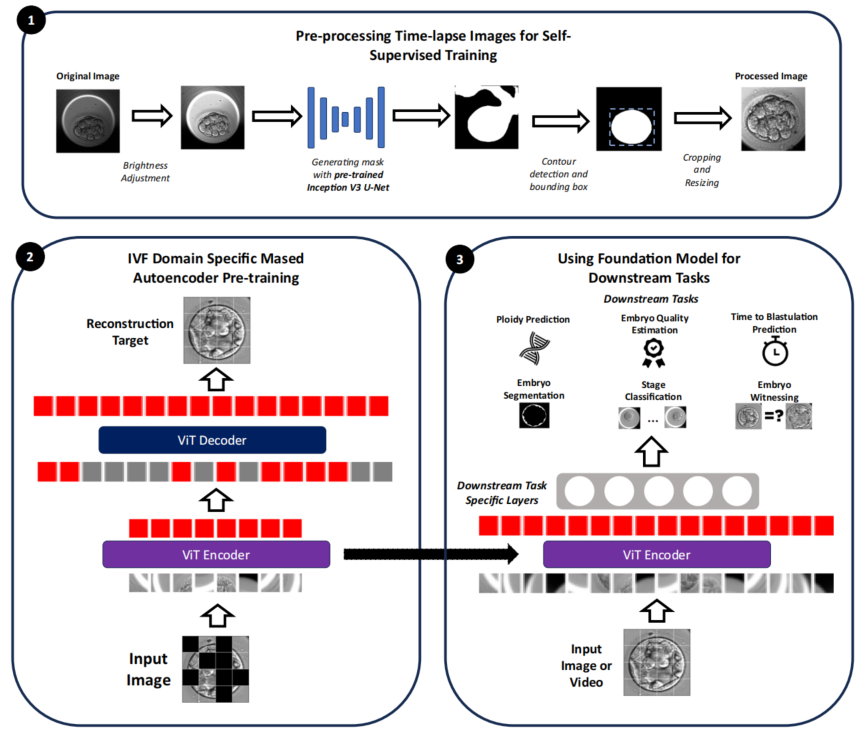

Research Methods: Enabling Machines to “Understand” Embryos First

The study adopts a two-phase strategy of “broad observation first, specialized training second” to construct the foundational model. In the first phase, the team used nearly 18 million unannotated time-lapse images (85-112 hours post-fertilization) for “image inpainting” training—where the system randomly occludes most regions and prompts the AI to infer the complete embryonic morphology from visible parts, fostering a holistic understanding of embryonic structure. In the second phase, a lightweight output module was added to the pre-trained “observation system,” and the AI was trained on hundreds to thousands of labeled samples to perform specific judgments (e.g., scoring or classification). The parameters of the foundational system were frozen, with only the terminal weights adjusted, preserving deep understanding while preventing overfitting on small datasets.

To evaluate FEMI’s real-world performance, the study designed multi-level comparisons. First, it was benchmarked against 12 mainstream models, including traditional supervised models (VGG16, ResNet101, EfficientNet, etc.), video analysis models (MoViNet), and existing IVF-specific AI (STORK-A). Second, comparisons were conducted with other self-supervised learning models to assess the actual gains of domain-specific pre-training in medicine. All comparisons were performed on six key clinical tasks using identical datasets, evaluation metrics, and four-fold cross-validation to ensure robust results. Test data covered five reproductive centers (with varying countries, equipment models, and operational practices) to verify the model’s generalizability across diverse scenarios.

Research Results: Strong Performance Across Multiple Tasks

- Ploidy Prediction: For complex aneuploidy identification, the model achieved 85% accuracy with video + age input, while the single-image model exceeded 75% accuracy on some datasets, offering a non-invasive screening alternative for resource-limited regions. For the subgroup of low-quality embryos (scored 10-14), FEMI achieved 67.7% accuracy. Interpretability analysis showed the model focused on cell boundary clarity, inner cell mass (ICM) compactness, and trophectoderm (TE) cell uniformity—aligning closely with embryologists’ judgment logic.

- Blastocyst Quality Scoring: Prediction error for ICM was reduced by 45% compared to existing models. Given the high subjectivity of ICM assessment, FEMI’s high precision demonstrates machines can stably learn complex evaluation rules. Video input showed distinct advantages in TE scoring, with prediction errors of less than 1 point for high-quality embryos and 2.04 points for low-quality embryos—outperforming the compared EfficientNet-V2 model.

- Embryo Matching: Achieved over 90% F1 score across a 96-112 hour time window, whereas previous similar technologies only worked within the narrow 105-110 hour range. The expanded time window means the system can reliably retrieve embryos even after prolonged removal from the incubator, reducing psychological stress and error risks in clinical operations.

- Blastocyst Development Time Prediction: With an error of approximately 6 hours, it sufficiently assists embryologists in prioritizing observation targets for the next day. Notably, embryos with smaller time prediction errors often exhibit normal developmental rhythms, showing a negative correlation with aneuploidy risk.

- Embryo Region Segmentation: Despite being trained on only 274 samples, FEMI achieved strong performance in zona pellucida and TE segmentation, with Dice coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.95—comparable to MedSAM, a specialized model for medical image segmentation.

- Stage Classification: Top-2 accuracy reached 90.8%, meaning the first or second prediction almost always matches the true developmental stage. This “fuzzy correctness” feature holds practical value in clinical practice.

Research Innovations and Limitations

Innovations

- FEMI represents one of the earliest attempts at foundational models in IVF. Universal features pre-trained on 18 million images can be transferred to all tasks, significantly reducing the demand for labeled data.

- Video-based dynamic analysis achieved 85% accuracy in non-invasive ploidy prediction, providing a potential alternative initial screening tool to PGT-A for resource-limited regions.

- Consistent performance across datasets from five countries with varying equipment and operational practices demonstrates strong generalizability.

- Quality scoring and stage classification adopt regression rather than classification, allowing prediction of intermediate states that better align with biological complexity.

Limitations

- Training data is primarily sourced from high-resource centers, lacking coverage of diverse culture conditions in low- and middle-income regions. Insufficient data on older patients may affect prediction stability for extreme age groups.

- Training is limited to 112 hours post-fertilization; predictive performance for day 6/7 blastocysts (which may be euploid) remains unvalidated, requiring extension of the time window.

- Quality scoring relies on embryologists’ subjective judgments as ground truth, meaning the model may replicate biases rather than objective “truth.”

- While attention maps indicate key focus regions, the overall decision-making logic remains a “black box” that requires more detailed biological interpretation.

Clinical Significance and Future Outlook

This study develops an efficient, non-invasive, and standardized AI-based foundational model for IVF embryo assessment. By demonstrating exceptional performance in critical tasks such as ploidy prediction, blastocyst quality scoring, and embryo verification, the model significantly reduces reliance on manually labeled data while maintaining strong generalizability across multi-center datasets. This not only improves the accuracy of embryo selection but also reduces misjudgments caused by subjective variability, providing patients with more reliable IVF treatment plans. Future directions include integrating time-lapse imaging, metabolomics, and genomics data to construct digital embryo twin models, advancing IVF from empirical medicine toward precision medicine.